All Systems Struggle

Collaborative Project | Webseries inspired by tokusatsu shows about CPU fighters in a tournament | Google Docs, YouTube, Super Smash Bros. Ultimate | All worldbuilding & episode writing/recording

All Systems Struggle (often abbreviated to just ‘ASS’) is a collaborative multimedia webseries that uses Super Smash Bros. Ultimate and the fights between CPU characters to tell part of the story, formatted in the style of a TV anime or tokusatsu show, complete with opening and ending sequences. With its conception beginning in late 2021, The series itself is about a tournament show of the same name, led and hosted by Tera and Daigo, as they deal with bizarre fighters, evil corporations, and destructive devices that look like childrens’ toys. Additionally, viewers and readers can submit their own characters to be included in the series. However, whether they leave a massive impact on the overarching plot as a whole is entirely dependent on how they perform in battle. Episodes are largely written in Google Docs with battles uploaded to YouTube placed in-between certain sections.

Capturing the

Saturday/Sunday Morning Feeling

One of the biggest goals I set for myself with ASS is to reflect my own experiences in watching a series as it airs and sharing it with some friends, sometimes even watching it together. Primarily, I based these experiences off my years of watching Kamen Rider and Super Sentai. That’s why, at the beginning of each episode, a disembodied voice talks to you about watching the show.

The other biggest goal I had in mind was to make this feel like as much of a tokusatsu production as possible, despite the limitation of writing these episodes in Google Docs. I wanted audiences to experience that same excitement, drama, and whimsy of tokusatsu just like I did. One step was extremely obvious: make devices that look like children’s toys that make cool noises and equip wearers with a suit of armor that has a specific “design” motif (dragons, swords, cellphones, etc.).

Then there’s the logo for the show. I commissioned Stefanus Hendy, a graphic designer who’s done work for various online streamers. I based the logo design off certain Kamen Rider title logos for specific seasons: a metallic outline, sharp angles, writing the title in English and Japanese…

And then comes the opening and ending sequences.

I added these for two reasons. One is to match the productions as closely as possible, as you need a good opening for your show, same with a good ending. The other is because I think they’re really cool and I tend to imagine certain songs as animated sequences when I listen to them. I had prior experience with editing videos in this style, and I decided to use Super Smash Bros. Ultimate’s in-game video and image editors for certain shots, angles, and scenes. I even included subtitles for each song that you can sing along to in both English & Japanese, and a “sponsor” segment at the end of the opening.

I felt like that would make it feel more “authentic.”

The last few details are mostly minor. Episodes are usually released every Sunday, which is the usual day new Kamen Rider episodes drop, even though it’s usually every Saturday in Japan due to time zone differences. Some characters in the series have “insert themes,” songs that play when a character is doing something really cool and wants to be extra dramatic about it.

All of this, because I felt like adding them to make it more like a tokusatsu show.

Collaboration & “Fanfuffles”

ASS is a collaborative series, meaning that audiences can submit their own characters with their own backstories and personalities and secrets for the show to use, to see what happens if those characters interact with this world. ASS is a “fanfuffle,” a fan-made term for tournament shows similar to CPU Kerfuffle by Jenny Chongo, a livestreamed series with a similar premise: CPUs in Smash Ultimate fighting in a tournament while growing and changing, creating narratives out of completely random events. This concept isn’t really anything new, there have been plenty of others that have done the same thing to varying degrees and using other games.

A lot of fanfuffles share a world in a fictional version of the United States where things like magic, werewolves, ghosts, and deities visiting mortals are common occurrences. When something big happens in one show, it affects all others to some degree, such as Utah becoming a bottomless hole in the ground after it was destroyed by a beam of light created by a god defending himself from harm. Some characters from one show make special guest appearances in other shows. Certain performances during these tournaments such as one fighter practically sweeping the other and mopping the floor with them result in a variety of things: secrets are revealed, plots are developed, characters transform into other fighters, something might come later down the line because of this performance.

Fanfuffles are a shared community of shows, to put it simply.

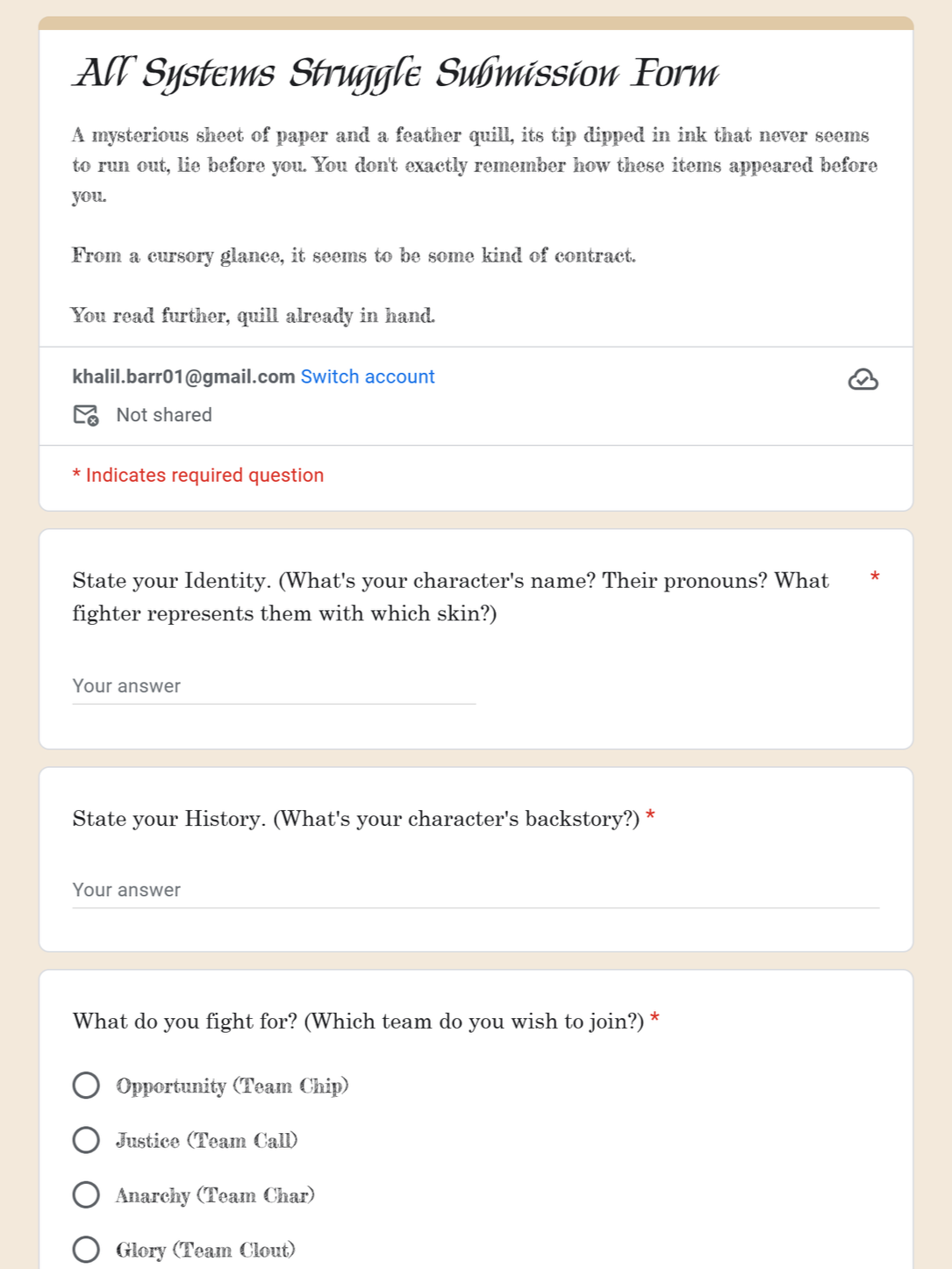

Like many fanfuffles before it, ASS takes in submitted fighters and adds it to its roster with their selected character on their selected team, their appearance, their insert themes, and any other details they might have.

Unlike the livestreamed fanfuffles, where tournaments are hosted via Discord calls and the people in the call voice act characters that they chose, ASS is a written fanfuffle made by a single person (me). There’s an implicit trust between the submitter and the writer, where their interpretations of the same character may differ in certain ways. Of course, we can all talk to each other to give suggestions about how a character should act. But for the most part, submitters are handing all control over to me. The same happens in the livestreams, where a character’s demeanor or attitude is almost entirely based on the information they get via their descriptions.

To put it in blunter but lighthearted terms, we’re a group of friends acting out plays and writing stories of us playing with dolls.

Improvisation &

CPU Performance

It’s been mentioned before, but it bears repeating. Every single character in a fanfuffle is controlled by a CPU player, usually set to the highest difficulty but there have been exceptions, meaning that it’s the battles between these CPUs that tell the story. It’s like stat-tracking in sports in a weird way, creating narratives out of numbers and random events.

Two fighters had a close match? Oh, they must have known each other before the tournament. One fighter starts doing risky moves and completely dominates the other? Well, that fighter’s is now a daredevil and will seek to win at any cost. One fighter stood around and did nothing for a full minute because the CPU had a bit of a malfunction? That character is a pacifist or feels bad for the other fighter for some reason.

Whatever happens, happens. And whatever happens is recorded in the history of the show.

But sometimes, the person making the fanfuffle has a certain plan for how they want certain plot beats to go. They want the story to go in a certain direction because they’ve had so many ideas based on the characters they received. But there’s a problem.

The CPUs are unpredictable.

Sometimes, it’s hard to get the CPUs to do what you want because they might do something completely different. The strongest character might be defeated easily by a joke character, despite the intention being that the strongest character has to win everything. So in order to minimize this issue, you alter elements outside of the fight to be as close to that plan as possible while still maintaining the general spirit of improvisation. You power up a fighter, you weaken a fighter, you give a fighter a handicap, you alter the rules to give someone as much of an advantage as you can.

Now, some may say that this could ruin the spirit of shows like this, where the unpredictability of the CPUs is the point of it all. Of course, the CPUs doing their thing is how we get these emergent narratives in the first place. But the thing is sometimes, letting the CPU always do its thing might diminish the impact of certain events or weaken the narrative. A balance is needed, just like in any collaborative work, even if you’re the only person working it. Let your actors do most of the work, but be sure to nudge them in the right direction from time to time.