Midnight Witch Starlight

College Project at DigiPen | Narrative & Level Design, then Design Lead | 2D run & gun game about a fake magical girl anime from the 90s | Custom engine | Team size: 11-15 | Worldbuilding, lore, character profiles, example dialogue | Led the charge in revising the game aesthetic & theme

Midnight Witch Starlight is a 2D sidescrolling run and gun game inspired by ‘90s anime about a magical girl fighting against the forces of darkness, made in my first big game project class that would span for two semesters, leading to a development cycle of eight months. However, I was rapidly promoted to be the game’s Design Lead after another designer that was working on Systems, UI, and UX had to leave during the Spring semester half of the dev cycle.

Switching Gears

Before Midnight Witch Starlght, the game was titled MagiCraft. The premise remained the same: it was a ‘90s anime-inspired magical girl game. However, during development, we discovered two problems. The first was that you don’t really craft in the game. You have spells and you could combine them, but you don’t craft magic. The second was that it really did not seem like a “magical girl” game. The main character looked like a mage with a witch’s hat and robe, but they weren’t a traditional-looking magical girl. No frilly outfit, no skirt, no wand that looks like a toy, no ribbons… None of that. When we got feedback that addressed these specific things, we had to pivot. But we as a team were struggling a little bit as to how we should pivot.

So, I decided to take charge and focus on the narrative and flavoring aspect of the game.

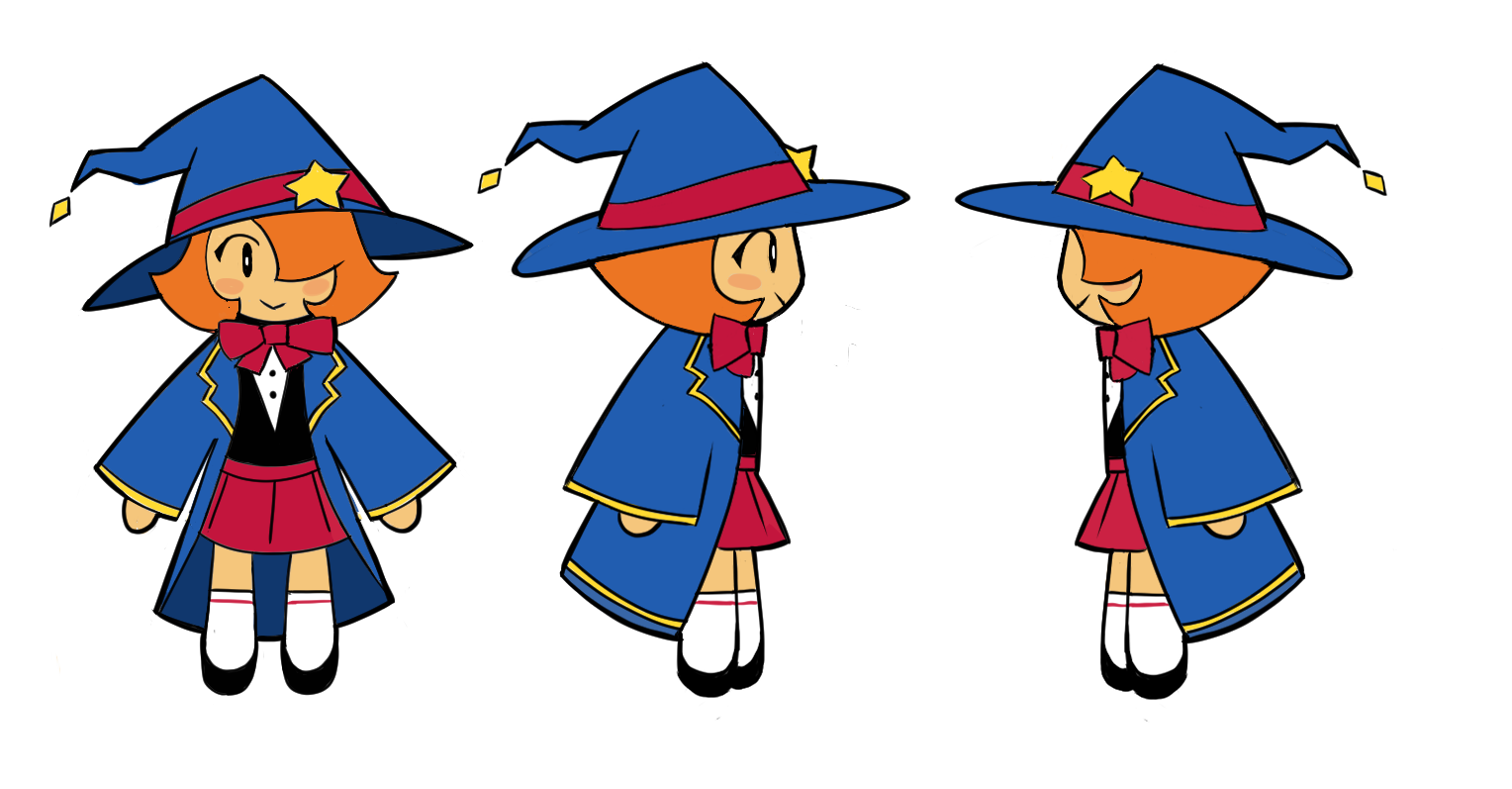

Since the team formed, I was the Narrative Designer for the game. I was in charge of writing the worldbuilding, the characters, the backstory, all of it. Ever since we received that feedback, I took charge in making everything seem more like a magical girl anime. The first was directing the redesign for the player character, the titular Midnight Witch, Starlight. As mentioned, she had the appearance of a mage and not a magical girl. So, using inspiration from classic magical girl anime like Sailor Moon, Cardcaptor Sakura, and Mysterious Thief Saint Tail, I directed the art team to reflect those character designs more.

The second was the title. Since MagiCraft doesn’t work and the game needed to be more “magical girl”-y, I rewrote the game’s title to be what it is now: Mignight Witch Starlight. This too is supposed to reflect its inspirations and 90s contemporaries; examples like Flower Witch Mary Bell, Magic Knight Rayearth, Saint Tail from earlier, Revolutionary Girl Utena.

Third and finally, I redesigned the logo. I provided a draft for the art team to incorporate all of the changes we’ve decided on: our pivot to the “midnight” theme by adding a crescent moon and keeping the MagiCraft font for our new title.

And that’s how Midnight Witch Starlight became the game it is today.